Over the past two years, Stray Dog Institute has implemented many principles and practices of trust-based philanthropy in our grantmaking and relationships with nonprofit partners. Here, we share what we have learned about trust-based philanthropy, how we have implemented a trust-based approach, and what lies ahead as we continue to embed trust-based practices into our work.

What Is Trust-Based Philanthropy?

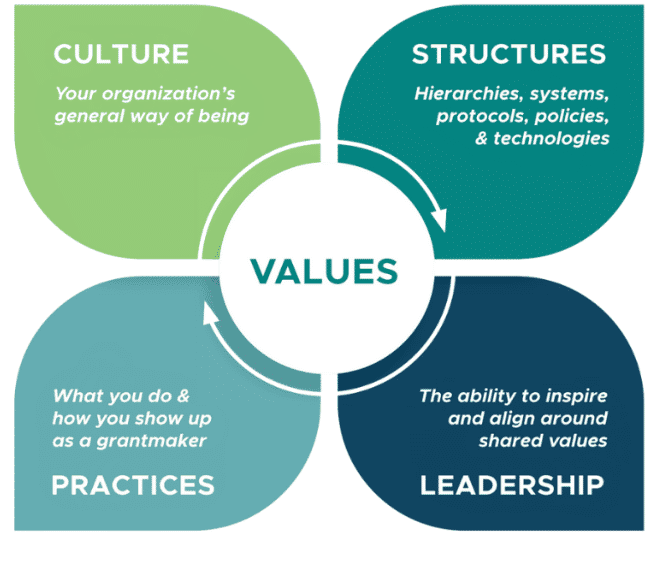

Stray Dog Institute’s embrace of trust-based philanthropy has been strongly influenced by the Trust-Based Philanthropy Project (TBPP), an invaluable resource for inspiring and evaluating a foundation’s relationship-building and grantmaking. “At its core,” TBPP explains, “trust-based philanthropy is rooted in a set of values that help advance equity, shift power, and build mutually accountable relationships.” A trust-based approach to philanthropy engages both a foundation’s values and practices. An organization’s values undergird its approach to relationships and grantmaking, while trust-based practices put a foundation’s values into action.

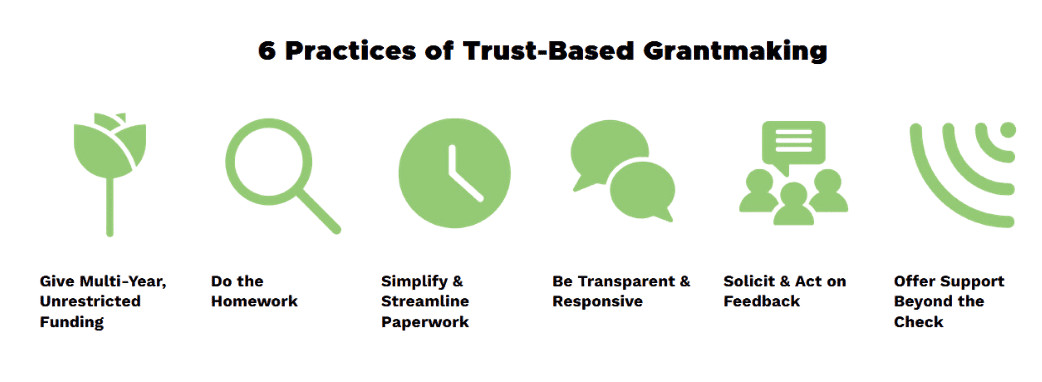

Images courtesy of the Trust-Based Philanthropy Project.

Trust-based philanthropy recognizes the inherent power dynamics between nonprofits and foundations, many of which are “an expression of the social, political, and economic inequalities that many of our nonprofit partners are working to resolve.” The approach aims to help funders and nonprofit partners redistribute the power between them and, on a larger scale, dismantle structures of bias and inequity in philanthropy. As a result, trust-based philanthropy can help funders and grantee partners create more open, honest, and ultimately more effective relationships with each other.

Relationships

The cornerstone of Stray Dog Institute’s approach to trust-based philanthropy is a spirit of partnership with and service to our nonprofit partners and the movement. While our own team has a breadth and depth of knowledge in the food system transformation, nonprofit, and philanthropic spaces, we know that our nonprofit partners are the experts in their issue areas. We approach our philanthropic interactions with humility and an openness to learning and growing. Because we recognize the expertise of our partners, we make it clear that we do not expect them to mold their work based on our interests or preferences as a funder. But we do hope we can offer collegial advice and feedback.

Elevating Partner Perspectives

Funders, influenced by classist, patriarchal, and white supremacist values that have historically permeated the philanthropic sector, frequently prioritize their own perspectives over those with subject matter expertise and/or lived experience. As a result, a (thankfully, changing) norm in philanthropy has been for grant-funded nonprofits to defer to funders’ preferences and interests and even shape work accordingly to secure funding. The expectation that grant-seekers will prioritize funders’ perspectives and comfort deepens the power divide between funders and nonprofits—putting funders unfairly on a pedestal and closing off opportunities for genuine partnership, mutual learning, and communication between funders and grantees.

From our inception in 2019, Stray Dog Institute has worked to reject this harmful power dynamic in our grantmaking and relationships with nonprofit grantee partners. Instead, we engage nonprofits in a spirit of partnership and have embedded this value in our approach. We consider ourselves supporters of—and collaborators with—our partners, working with them toward shared goals.

Working in a spirit of partnership has allowed Stray Dog Institute to meaningfully engage our nonprofit partners to help determine how and where we can best serve the movement for food system transformation. Perhaps our best illustration is the Roundtable on Animal Agribusiness Reform, co-hosted in 2019 by Stray Dog Institute and the Yale Law, Ethics, and Animals Program. The Roundtable brought together 30+ leaders from the food system transformation movement to identify key opportunities for reform within the US industrial animal agriculture system.

The issues identified by the Roundtable attendees became Stray Dog Institute’s main areas of focus for the following two years, during which we convened three working groups of movement leaders that crafted strategic roadmaps for funders and movement allies. Some work in these areas will likely continue at Stray Dog Institute for several years.

We continue to actively engage our grantee partners about how our focus areas and practices can most effectively serve them and the movement. Working in a spirit of service helps us stay open and flexible to the needs of our partners and the movement.

Offering Thought Partnership

In addition to informing our strategic priorities, Stray Dog Institute seeks to engage in thought partnership whenever helpful to our grantee partners. This is one of the ways we put Support Beyond the Check—one of trust-based philanthropy’s Six Core Practices—into practice. Being a thought partner is exactly what it sounds like, but it looks different based on each unique relationship and our collaborators’ desires. As thought partners, the Stray Dog Institute team has served as a sounding board for organizations as they hone their theories of change and focus areas, provided feedback on fundraising materials and pitch presentations, and provided resources and insights on strategic planning and nonprofit management, as just a few examples. As a private operating foundation, we have the capacity to actively engage through collaborations like working groups, salons, joint research projects and publications, and more.

When Stray Dog Institute engages as a thought partner in any capacity, we strive always to be aware of the power imbalance between our nonprofit partners and us and are committed to alleviating it. When we discuss possibilities for collaboration, we name the funder-grantee power dynamic explicitly and share our commitment to thought partnership and to prioritizing and valuing their expertise and leadership. Where additional dynamics, such as race, are at play, we also acknowledge and try to address them.

Grantmaking

The Trust-Based Philanthropy Project describes six core practices that funders can use to implement a trust-based approach in their grantmaking:

- Give multi-year, unrestricted funding: The work of nonprofits is long-term and unpredictable. Multi-year, unrestricted funding gives grantees the flexibility to assess and determine where grant dollars are most needed, and allows for innovation, emergent action, and sustainability.

- Do the homework: Oftentimes, nonprofits have to jump through countless hoops just to be invited to submit a proposal. Trust-based philanthropy moves the onus to grantmakers, making it the funder’s responsibility to get to know prospective grantees, saving nonprofits time in the early stages of the vetting process.

- Simplify and streamline paperwork: Nonprofits spend an inordinate amount of time on funder-driven applications and reports, which can distract them from their mission-critical work. Streamlined approaches focused on dialogue and learning can pave the way for deeper relationships and mutual accountability.

- Be transparent and responsive: Open, honest, and transparent communication supports relationships rooted in trust and mutual accountability. When funders model vulnerability and power consciousness, it signals to grantees that they can show up more fully.

- Solicit and act on feedback: Philanthropy doesn’t have all the answers. Grantees and communities provide valuable perspectives that can inform a funder’s strategy and approach, inherently making our work more successful in the long run.

- Offer support beyond the check: Responsive, adaptive, non-monetary support bolsters leadership, capacity, and organizational health. This is especially critical for organizations that have historically gone without the same access to networks or level of support as their more established peers.

Providing Unrestricted Funding

Providing unrestricted, multi-year funding is a characteristic practice of trust-based philanthropy. As John Esterle from the Whitman Institute explains, providing unrestricted funds allows partnerships between funders and nonprofits to start from a place of trust rather than implicit distrust resulting from funders’ lack of respect for nonprofits’ expertise. Over the past two years, Stray Dog Institute has shifted our grantmaking toward mostly unrestricted grants (see the “Challenges” section on our experience with multi-year commitments). We recognize the importance of general operating support and trust our grantee partners to determine what is best for their organizations and the movement.

Of course, trust does not replace diligence. In choosing to support an organization, we do our homework (another TBPP-recommended practice) to determine whether an organization is the right fit for us to support. Trust is also dynamic. In the rare case that a partner engages in work that we strongly oppose (e.g., partnering with an organization that has actively harmed members of our movement), we have a conversation with that partner to understand their perspective better and decide whether it makes sense to continue our relationship.

Stray Dog Institute has received positive feedback from many partners related to providing unrestricted funding. Nonprofits have shared that general operating support makes their budgeting processes easier, that unrestricted funds support vital work that is often under-valued by funders, and that it gives organizations the latitude to work on projects that they are excited about and have found successful rather than constantly coming up with new ideas to pitch to funders. In the cases where project-based funding is appropriate, we are committed to working collaboratively with our grantee partners and recognizing their expertise.

Reducing Burdensome Structures

Flexible and minimally burdensome communication structures are another way that Stray Dog Institute has aimed to implement trust-based practices in our relationships with grantees. For grants of $10,000 or less (a majority of our grants), Stray Dog Institute does not require formal reporting, but we welcome opportunities to learn from and engage with grantee partners. For grants greater than $10,000, we work with our partners to determine a minimally burdensome communication structure. This may include substituting calls for reports and accepting written materials developed for other funders.

Additionally, Stray Dog Institute does not require applications from nonprofits to be considered for funding. While we do not currently have a Request for Proposal (RFP) process, we do accept unsolicited proposals via our Contact Form.

Relatedly, to reduce the perpetuation of inequities in the types of organizations we fund, we have made it a practice to ask our nonprofit partners and other movement leaders to share with us organizations that they think we should consider funding. We keep track of the organizations recommended, those we ultimately fund, and those that are BIPOC[i]-led.

Promoting Transparency

Increasing transparency about our grantmaking practices and other internal topics has been an area of significant growth over the past few years for Stray Dog Institute. Historically, we provided little information publicly about our grantmaking practices and organizational priorities that were not required by law. We recognize, however, that transparency can help build trust and mutual accountability and lessen power dynamics between funders and grantee partners. On a larger scale, we also recognize that historically in the philanthropic sector, funders have expected nonprofits to provide high levels of transparency while providing little transparency themselves.

To be more open about our grantmaking practices, Stray Dog Institute recently added a “Grantmaking” page to our website, which details our philanthropic philosophy and answers FAQs about our grantmaking. Although there are certain details that we chose not to share publicly, our team thoughtfully considered what we should share and pushed some of our previously held boundaries.

In addition to increased transparency on our website, we aim to provide transparency in our philanthropic relationships. We often ask trusted nonprofit partners for insight on challenges or tough questions we are considering, as well as areas where we recognize there are gaps in our knowledge. We also aim to be as transparent as possible regarding funding commitments. Though most of our grants are renewed on an annual rather than multi-year basis, we try to give our grantee partners as much information as possible, as early as possible, about future funding commitments and amounts, even if with the caveat that decisions are yet to be finalized. We are particularly committed to providing this transparency and advance notice when our funding must change significantly or when a multi-year commitment is coming to an end.

Challenges

In the spirit of transparency and vulnerability, we would like to share some of the challenges we have faced in bringing a trust-based approach to our work. We recognize that there is no such thing as a perfect embodiment of trust-based philanthropy. An expectation of constant perfection can be considered a symptom of White Supremacy Culture, as defined and written about by Kenneth Jones and Tema Okun. Instead, implementing a trust-based approach is a constant process of learning and growth.

Committing to Multi-Year Funding

While Stray Dog Institute has shifted to unrestricted funds for the majority of our grantmaking, most of our grants continue to be committed on an annual rather than multi-year basis. TBPP recommends that funders provide multi-year, unrestricted grants, as “long-term, flexible funding allows organizations to allocate resources where they are most needed, making room for innovation, emergence, and impact.”

While we recognize the benefits of multi-year funding commitments, shifting a majority of our funding to multi-year commitments presents a practical challenge to Stray Dog Institute. As a smaller foundation whose resources depend closely on market conditions, the amount of funds we can give varies year-to-year. It is important to us to honor the commitments we make to our nonprofit partners. It would be risky to always make multi-year commitments when our budget fluctuates annually.

While we cannot provide multi-year commitments for all our grants, we have offered multi-year commitments for some. In particular, we have provided multi-year commitments for special projects that need a longer runway for starting up and innovation. These commitments allow our partners to successfully launch new programs and initiatives that they may not otherwise have been able to begin without a multi-year funding commitment. This long-term support has also allowed our partners to focus their time on developing their programs and building relationships with other funders to ensure the longevity of their work.

Although we do not make multi-year commitments for most of our grants, Stray Dog Institute typically provides year-on-year support to our nonprofit partners. An area where we hope to grow is considering multi-year commitments for our partners for whom a multi-year grant might be especially beneficial, such as new organizations, historically underfunded sectors, and/or BIPOC-led groups.

Soliciting and Acting on Feedback

Soliciting and acting on feedback is one of the six key pillars of trust-based philanthropy. In the words of the TBPP, “a foundation’s work will be inherently more successful if it is informed by the expertise and experience of grantee partners and communities.” Soliciting and acting on feedback is perhaps the pillar of trust-based philanthropy that Stray Dog Institute has implemented the least. While we frequently ask our close partners to provide us feedback on how we could better serve them and the movement and act on that feedback accordingly, we do not have a formalized process for collecting feedback or reporting on how it informed our thinking and actions.

One reason why Stray Dog Institute has not yet implemented this change is that we are a relatively new organization, and we continue to develop our internal processes. We have also been hesitant to ask more from our nonprofit partners. However, we realize that having a mechanism that allows our partners to provide us feedback in a safe, anonymous, and voluntary way would help us ensure we are serving the movement in the best ways possible. Just as important as collecting feedback, and perhaps more so, is being accountable for acting on it and sharing how it impacted us. Thoughtfully considering ways we could solicit and act on feedback from our partners is an element of trust-based philanthropy we are committed to exploring in the coming year.

Conclusion

As Stray Dog Institute has broadened and deepened our relationships in the food systems transformation and farmed animal advocacy movements, trust-based philanthropy has been an invaluable tool for learning, self-reflection, and growth. We hope that sharing our reflections on implementing a trust-based approach demonstrates our commitment to breaking down inequitable power structures in philanthropy and constantly learning and growing as partners. We also hope that this window into our journey provides an opportunity for our fellow funders to reflect on ways they already bring trust-based values and practices into their work, and ways they might lean in further. Finally, we are deeply grateful to the Trust-Based Philanthropy Project and its partners, who inspire and inform our work and demonstrate the many different forms trust-based approaches can take.

In the spirit of transparency, if you would like to share your thoughts on our approach or provide feedback on this blog post, please reach out to us via our Contact Page. We would appreciate hearing from you.

[i] Stray Dog Institute uses the term BIPOC to recognize the lived histories of oppression and resistance experienced by Black, Indigenous, and People of Color. This term is not universally embraced, particularly because it can erase the experiences of individual groups by lumping them together. Additionally, the language of this term reflects the specific historical social context of the United States and may not accurately reflect current or past racial and ethnic descriptions elsewhere. We recognize these drawbacks and use the term BIPOC only when a statement is truly applicable to Black, Indigenous, Latinx, Middle Eastern, North African, East Asian, South Asian, Southeast Asian, and Pacific Islander communities in the US. When an experience or condition is applicable only to a specific group, we use specific rather than general language.