Editor’s Note

Stray Dog Institute supports the movement for food systems transformation to benefit people, animals, and the environment. In this guest post, Farm Action explores the consequences of basing the US food system on prioritization of industrial feed crops for intensive animal agriculture. Farm Action’s analysis explores the negative consequences that public financial support for industrial feed crops creates for farmed animals, farmers, rural communities, environmental sustainability, and the fight against global hunger.

Picture a typical dinner table at your home or in your neighborhood. Now think about where the food on that table came from. Are you and your neighbors able to buy fresh, healthy food from local farms? Or is it more likely that your dinner ingredients traveled a great distance from a big industrial farm to a big box store?

The food that is readily available to communities nationwide is shaped by an array of laws and regulations. These agricultural policies direct federal dollars to certain kinds of crops and farming methods.

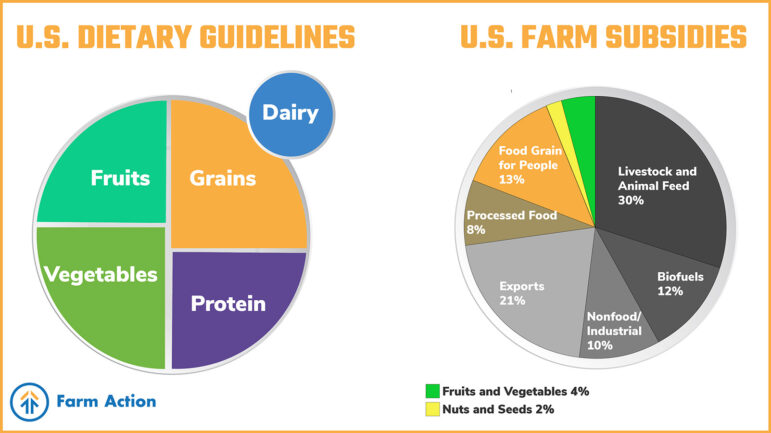

Here is a little-known fact: There is actually a glaring contradiction between the kind of food the US government recommends and the kind of food it supports. The USDA recommends filling 50% of your plate with fruits and vegetables, but only 4% of federal farm subsidies supported their production in 2019.

Meanwhile, industrially produced meat, poultry, eggs, and animal feed received 30% of federal farm support dollars in 2019. This number is likely an underestimation of how much funding industrial livestock production absorbs. It does not account for exports, and feed and meat are both leading export items for the US.

To understand why this contradiction exists, one must look at the mechanisms that direct government support toward some foods and not others—and the consequences of this arrangement.

Prioritizing Cheap Feed for Big Meat

The US food and farm incentive system determines which foods receive production support through subsidies or taxpayer-backed financial assistance. Subsidies help keep prices low, so they eventually determine what kind of food will be accessible and affordable to consumers.

Currently, the government directs the bulk of its subsidies toward commodity crops like corn and soybeans. Some of these are used to make cheap sugars, starches, and oils that end up in highly-processed, low-nutrition junk foods marketed by agribusiness corporations. About 42% of US corn and 30% of US soybeans become industrial livestock feed, the key component of a financial mechanism called the “Feed-Meat Complex.”

Here is how it works: Billions of dollars of American taxpayer money are directed toward commodity payments each year. In 2019, $3.3 billion went to subsidies for corn, and $1.5 billion went to subsidies for soybeans. All this available funding ensures that the US farm system will produce plentiful cheap corn and soybeans.

Consolidated meatpacking corporations buy up this crop of corn and soybeans and feed it to animals, reaping record profits. The less they spend on feed for their livestock and poultry, the bigger their profit margins become.

Having taxpayers subsidize their feed costs benefits these corporations, so they lobby to keep those subsidies in place. Only four corporations control 85% of the beef processing industry, granting them anti-competitive leverage over the market as well as clout on Capitol Hill.

Unfortunately, the Feed-Meat Complex has contributed to the rapid loss of America’s independent family farms. About 4 million farms went out of business between 1935 and 2012—while the average farm size more than doubled.

The power dynamics in agriculture have also changed drastically in that time. Now, it is common for the business of farming in the US to be conducted via contract between a farmer and a powerful, consolidated agribusiness corporation. These arrangements often trap farmers in unstable financial arrangements with oppressive debts, stripping them of their autonomy to decide what crops to grow or how to raise livestock or poultry.

You Get What You Pay For

Government support for industrially produced meat and processed food has helped the Feed-Meat Complex become the dominant feature of US agriculture. As taxpayers, the US public subsidizes this system of industrial agriculture and industrial animal production—even though it causes harm throughout the food system.

Industrial agriculture is not the best system to feed the world—it is merely the one with the most government and corporate support.

Industrial Agriculture Harms Animals

Industrial meat production inflicts abusive conditions on animals for the duration of their short and uncomfortable lives. 99% of livestock and poultry in the US are raised in Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs), where they are confined, often indoors, for long periods of time in crowded conditions that lead to stress, sickness, and sometimes death.

Pigs are remarkably intelligent, but industrial operations confine them to crates with hard floors that prohibit natural behaviors like rooting. Female breeding pigs are confined in gestation crates barely big enough to hold them, which prevent them from turning around and increase the likelihood of sores and ulcers.

Federal animal protection laws do not apply to any birds, leading to nightmarish conditions. Most chickens raised for meat live their lives indoors in poorly ventilated sheds. The unhealthy conditions and artificially rapid growth lead to chronic issues like heart failure and leg weakness, and many cannot support their own weight. Egg-laying hens are packed ten to a cage. Hens’ beaks are often burned or cut off to discourage cannibalism.

Turkeys, which in industrial operations have been bred to prioritize the growth of breast meat, are induced to grow so quickly that they often cannot walk or breathe sufficiently. Similar to chickens, turkeys raised indoors develop abnormal behaviors such as cannibalism.

Industrial Agriculture Harms Public Health

The industrial, corporate-controlled food system that has grown out of US agriculture policies is not designed to make healthy fruits, vegetables, and proteins accessible or affordable. For example, the USDA classifies fruits and vegetables as “specialty crops.” Senator Cory Booker illustrates this issue by comparing the price of a Twinkie and an apple in a typical New Jersey corner store.

The results of our upside-down public spending priorities are clear when looking at US diets: Half of Americans’ caloric intake comes from ultra-processed, nutritionally poor foods made with the starches and sugars derived from corn and soybeans. Nearly 90% of the US population consumes below the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for vegetables, and 80% consume below the RDA for fruit. The average adult American male consumes 75% more protein than necessary, and the average adult American female consumes 50% more protein than necessary. Animal-based foods like meat, eggs, and dairy account for 70-85% of this dietary protein.

Eating the industrial, nutritionally poor, and highly processed food that the government subsidizes is taking a major toll on public health. Heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and certain types of cancer are the leading causes of preventable premature death nationwide. In 2018, the US spent $3.6 trillion on national health—and that number is projected to nearly double to $6.2 trillion by 2028.

Industrial Agriculture Harms Rural Communities

Small family farms that created jobs and generated wealth for their communities once dotted the landscape of rural America. Consolidation and industrialization have driven many out of business: between 1948 and 2015, the United States lost more than four million farms.

Instead of neighbors, many rural Americans now live near CAFOs that degrade the air they breathe—causing asthma and other respiratory ailments—the water they drink, and the lakes and rivers where they once swam or fished.

The myth that big agribusiness is good for rural economies does not stand up to scrutiny. Industrial operations owned by corporations typically source their building materials, labor, and inputs from far away, wherever they can be most cheaply produced. Few of the economic benefits of industrial agriculture remain in local communities.

Furthermore, whatever CAFOs contribute to a local tax base is more than offset by increased local costs caused by their operations. In addition to repairs to local infrastructure, such as roads not originally built to accommodate constant heavy truck and machinery traffic, CAFOs also decrease the property values of their neighbors, harming the well-being of rural families and reducing property tax receipts for local governments.

In truth, industrial agriculture is hollowing out rural America by robbing it of opportunities for future economic growth, displacing independent farmers, and discouraging new residents from settling there.

Industrial Agriculture Harms the Environment

Industrial agriculture is a system designed to quickly yield maximum economic benefits—even if it means sacrificing the long-term productivity of the land. The practice of industrial monocropping degrades soil, causing nutrient runoff into groundwater and freshwater sources. In Iowa, one of the leading producers of subsidized industrial corn and soybeans, 61% of rivers and streams are categorized as impaired or polluted.

As bad as that sounds, the byproducts of industrial agriculture are not contained within the corn fields. Agricultural runoff carried by the Mississippi River into the Gulf of Mexico accounts for 41% of the Dead Zone, a 6,000-mile stretch of oxygen-depleted water in which marine life cannot survive.

Feeding the World? We Are Not Even Feeding Ourselves

In defending their methods and the policies that facilitate them, global food corporations insist that without modern industrial agriculture practices like monocropping and CAFOs, there would be mass starvation across the globe.

First of all, it is a myth that the industrial agriculture system currently feeds everyone. Agriculture already produces enough food to feed everyone on the planet, yet 828 million people worldwide are going hungry. In the United States alone, over 15 million households experienced food insecurity in 2017.

A shift in government subsidies from feed grains for industrial livestock production toward vegetables, fruits, nuts, legumes, mushrooms, and cereal grains would allow farmers to grow food profitably for their communities.

Secondly, championing industrial agriculture’s vast output overlooks the detrimental effects of its operations and ignores what kind of food is being produced—and for whom. Almost 90% of cereal grains grown on US soil in the 2017 census of agriculture were used for purposes other than direct human consumption.

It is also a myth that industrialization lowers food costs for consumers. The hyper-concentrated supply chains owned by consolidated corporations are not designed to keep consumer prices low but rather to achieve higher profits for corporate shareholders. In fact, food prices are increasing at unprecedented rates: Between August 2021 and August 2022, prices for food at home increased 13.5%, the largest 12-month percentage increase since the period ending March 1979. While consumers have become increasingly cash-strapped since the pandemic, corporations have enjoyed their most profitable two years since 1950 as their profits jumped 35%.

As power over the food system consolidated into fewer and fewer hands, agribusiness’s ability to profit at the expense of consumers grew. While consolidation does not drive background inflation rates, consolidation gives dominant industry players like agribusiness the power to raise prices for their own benefit during times of high inflation. Between 2000 and 2020, general inflation increased by around 54%, but in the same timeframe, food prices rose almost 60%. In highly concentrated sectors, such as red meat, poultry, and egg, prices rose more than 70%. In 2022 alone, Americans faced a nearly 12% increase in grocery prices, and a 138% spike in egg prices has captured the nation’s attention in recent weeks.

This has all led to allegations of price fixing, which is a symptom of extreme industry consolidation. In case after case, meatpackers pay very small penalties in price-fixing lawsuit settlements compared to the record profits they make from these pricing schemes. For instance, Brazilian meatpacking behemoth JBS agreed to pay $72.5 million between two price-fixing settlements since the beginning of FY 2022. Meanwhile, their net income for the fiscal year ending on June 30th (FY 2022) was a whopping $4.382 billion—a 56% increase year-over-year.

To put the penalty into perspective, $72.5 million is only 1.65% of the company’s yearly gain. This would be the equivalent of making $43,820 from an unlawful market deal and only paying $725 as a penalty.

As long as monopoly corporations can arrange the food system to prioritize their own profits, industrial agriculture will never successfully feed the world—or even the nation. In 2019, the mighty US agriculture system racked up a trade deficit for the first time in 50 years. The USDA forecasts the US will again run a deficit in 2023 for the third time since 2019.

This growing deficit is driven by US dependence on imported Mexican fruits and vegetables. Two-thirds of the fresh fruit and one-third of the fresh vegetables sold in the US are imported. If the 80–90% of Americans who are not eating enough fruits and vegetables suddenly transformed their diets, the current national food system would be unable to meet the demand. This situation leaves Americans more vulnerable than ever to foreign governments and fluctuations in global trade. Dependence on food imports is a potentially serious national security issue.

Industrial agriculture is not the best system to feed the world—it is merely the one with the most government and corporate support.

What if the US Prioritized Food, Not Feed?

Reshaping national agriculture policies to prioritize food, not feed would make the US food system look different than it does today.

A shift in government subsidies from feed grains for industrial livestock production toward vegetables, fruits, nuts, legumes, mushrooms, and cereal grains would allow farmers to grow food profitably for their communities. Increasing financial and technical resources in the Farm Bill would help farmers transition away from industrial agriculture and toward conservation and regenerative practices. Changing the Farm Bill to require that certain conservation standards be met would ensure that independent farmers—not industrial agribusiness corporations—benefit the most from public federal crop insurance, commodity subsidies, and disaster payment programs. Over time, a more environmentally-friendly agriculture system would also be more resilient and less costly for taxpayers.

Prioritizing food, not feed, in public agricultural policy means supporting and scaling up alternatives that build resilient local food systems. There are already examples of what that support could look like: Currently, federal funding supports a very successful program that provides healthy foods to nutritionally deficient households. By supporting local farms, the Gus Schumacher Nutrition Incentive Program (GusNIP) fosters the growth of resilient independent food systems while helping Americans get the nutritious food they need.

With greater support for nutritious, locally-produced food, the US can have a healthier and more resilient food system, a more compassionate relationship with animals, and a healthier population. Prioritizing food rather than feed would allow independent farmers to do what they do best: feed their neighbors and communities.

Disclosure: Stray Dog Institute contributed funding to support Farm Action’s work in the United States.